Discover how Namib Desert wildlife thrives in extreme conditions – elephants, beetles, plants & more adapt uniquely to survive harsh environments.

GVI

Posted: July 9, 2024

Clare Woolston

Posted: March 8, 2019

Both are endangered. One is a predator. The other is prey. We delve into how this new relationship came to be, in Tortuguero National Park, Costa Rica.

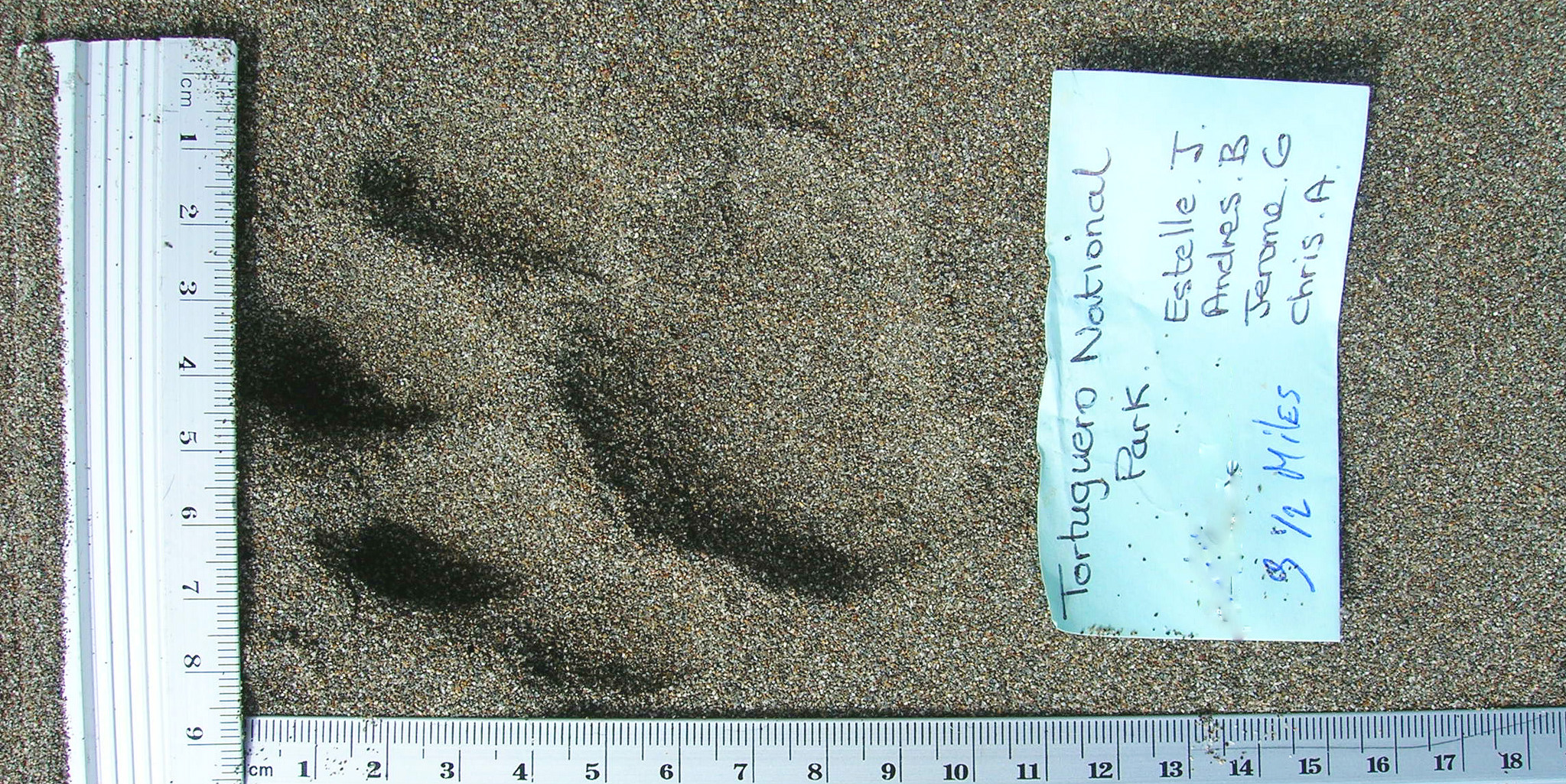

On the sandy beach of Tortuguero National Park, you find two sets of prints, and signs of a dramatic struggle.

One set belongs to an elusive, ghost-like hunter: the endangered jaguar. You track these, and soon enough, they intersect with those of a less cryptic species, the endangered green sea turtle.

Its carcass follows soon after, with scavengers picking through the remains.

But jaguars didn’t used to prey on green sea turtles in this area. So how did this relationship come to be? And is it affecting the green sea turtle population significantly?

Given the turtles’ endangered status, should the government intervene? GVI’s research helps to answer these questions.

In the 1990s, the land around Tortuguero National Park was modified. The agricultural frontier expanded as large-scale banana and pineapple plantations were established.

The jaguars were pushed into the park itself, and closer to the coast, where good habitat remained. This brought them closer to the turtles.

But proximity to something doesn’t necessarily mean you eat it. So what caused jaguars to switch from pursuing their main prey to eating turtles?

The answer is illegal hunting in the national park. This caused declines in the jaguar’s main prey species. Species targeted include the jaguar’s favourite, the white-lipped peccary (a pig-like animal). We know this from our research into the jaguar’s diet.

Jaguars are opportunistic predators. With less of their main prey around, they turned to what else was available: green sea turtles nesting on the beach.

And so this novel relationship between two endangered species came about.

In 1981, only one green sea turtle was reportedly killed by a jaguar at Tortuguero beach. Fast forward to 2013, and the average predation rate for green sea turtles has increased to 120 kills per year.

This data comes from GVI’s research collaboration with local partners in the region, including the Costa Rican Ministry of Environment, Energy, and Telecommunications (MINAET), Panthera and Coastal Jaguar Conservation.

We’ve developed these partnerships to help empower the local community to continue this research. Together, we’ve surveyed the beach weekly since 2005, to better understand this relationship between predator and prey.

Surveys are conducted by participants (both volunteers and interns) on our jaguar conservation project. Given the elusive nature of the jaguar, since 2010, we’ve used remote camera traps to capture and record their predation behaviour.

Each year, from February to November, our participants walk the 25-kilometre beach before dawn. They check camera traps set up to identify new or known jaguars in the area.

Each jaguar’s rosette markings are unique. We use these for identification. Any jaguar tracks are recorded. Our participants also collect jaguar scats (faeces) for use in feeding behaviour and genetic studies.

March to October is turtle nesting season. During this time, our participants monitor predation on sea turtles by jaguars.

When a turtle carcass is found, we note the species, and record the time and location. Camera traps are set up next to the carcass. This allows us to observe a common jaguar behaviour, returning to the kill.

As a result, we now have 14 years of predation data. We know that in 2010, only two jaguars were hunting sea turtles. Now, it’s 15.

Despite this increase, our research found that jaguar predation is not a significant threat to the local green sea turtle population. Greater threats are commercial fishing and illegal poaching.

In 1996, in Nicaraguan coastal waters, commercial fishing caused the death of 10,166 green sea turtles when they were caught as bycatch. Satellite tracking of Tortuguero beach green sea turtles shows that they migrate from the beach to their feeding grounds in Nicaraguan waters. This means the individuals killed as bycatch were most likely from the Tortuguero beach population.

In 1997, humans poached 1,783 green sea turtles from Tortuguero beach. In contrast, only four were killed by jaguars.

Despite these threats, the Tortuguero beach green sea turtle population has increased by 61% since 1986. So we know predation by jaguars is not having a significant impact. MINAET does not need to intervene to protect the turtles from the jaguars.

In 2010, we estimated the number of jaguars inside the Tortuguero National Park for the first time. We’ve identified the availability of their prey species and how important the white-lipped peccary is to the jaguar. We’ve observed changes in jaguar feeding behaviour over time. We now have a long-term data set on annual predation rates.

With our research continuing, we’ll monitor trends in predation rates by jaguars: either due to the number of jaguars in the area, a lack of preferred prey, or an increase of jaguars eating turtles.

This will help MINAET know if they need to act to actively manage this new relationship. For example, if illegal hunting increases and jaguars predate more on the turtles, MINAET will know that a greater focus on surveillance for illegal hunting is needed.

If you want to make a difference for these species, volunteer with GVI and join our jaguar conservation project. Or join one of our community-led sea turtle conservation projects in Costa Rica, Thailand, or Seychelles. Sign up now.

Discover how Namib Desert wildlife thrives in extreme conditions – elephants, beetles, plants & more adapt uniquely to survive harsh environments.

GVI

Posted: July 9, 2024